Looking Back: A Historical Perspective

By Naomi André, Ph.D.

|

| The cast from National Negro Opera Company's 1941 production of Aida. |

The opera world is currently presenting more productions that articulate African American experiences than ever before. Companies around the country are staging works such as Fire Shut Up in My Bones, Charlie Parker’s Yardbird, and The Central Park Five, to name a few. Therefore, Seattle Opera invited our Scholar-in-Residence, Naomi André, to place Black Opera in historical, contemporary, and future perspectives. This article by André is the first of a three-part series. In this essay, André highlights several historic milestones in Black Opera. Her second article—to be published in the Blue program—will investigate contemporary titles and artists. In her final piece—published in The Marriage of Figaro program—André speculates on future Black Opera stories and productions.

Naomi André is a professor at the University of Michigan, where her teaching and research focuses on opera and issues surrounding gender, voice, and race. Her writings include topics on Italian opera, Schoenberg, women composers, and teaching opera in prisons. Her latest publication is Black Opera: History, Power, Engagement.

How does one think about a history of Blackness in opera? “Black Opera,” what I like to think of as the construction of Black experiences in opera, encompasses a variety of activities, such as operas by Black composers and librettists with stories about Black people sung by Black singers. Yet having Black people involved in all these facets is not the only configuration. Black Opera can also include interracial partnerships that involve non-Black collaborators; for example, works incorporating Black narratives by non-Black writers or productions where, even if a character’s race is not specified as Black, opera companies give Black singers the opportunity to perform.

African American achievement is often marginalized and lost to the passage of time. Therefore the history of Black Opera is still being researched and written, so any narrative is going to be incomplete until more work is done. Happily, numerous recovery efforts are underway. To get a big picture of Black achievement in opera, it is helpful to focus on the various components of opera performance—compositional teams (composers and librettists), performers (singers, conductors, members of the orchestra), opera companies, choral societies that feed into opera performance, and behind-the-scenes artists who direct, costume, light, and build the production.

Where shall we start? For this foundational background, I’m going to set the scene by focusing on Black participation in opera in the United States from 1819 to 1955. To organize this discussion, I will focus on Black opera companies, singers, and composers.

Yet even earlier than the Civil War, Black involvement in opera includes vocalists who sang opera arias in concert and recitals. Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield (c. 1819–1876) was born into slavery, manumitted, and given voice lessons, ultimately becoming the first Black singer to have international success. Other Black opera singers of the 19th and early 20th centuries include Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones (1868–1933, also known as the “Black Patti”), Thomas Bowers (c. 1823–1885), Marie Selika Williams (c. 1849–1937), and several others Black singers, despite the nearly impossible odds against them. Sissieretta Jones toured the United States, Canada, Europe, and parts of the Caribbean. She sang for presidents Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt. From 1896–1915 she was the leading soloist of the Black Patti’s Troubadours, a troupe that performed vaudeville acts as well as arias and choruses from grand opera.

African American achievement is often marginalized and lost to the passage of time. Therefore the history of Black Opera is still being researched and written, so any narrative is going to be incomplete until more work is done. Happily, numerous recovery efforts are underway. To get a big picture of Black achievement in opera, it is helpful to focus on the various components of opera performance—compositional teams (composers and librettists), performers (singers, conductors, members of the orchestra), opera companies, choral societies that feed into opera performance, and behind-the-scenes artists who direct, costume, light, and build the production.

Where shall we start? For this foundational background, I’m going to set the scene by focusing on Black participation in opera in the United States from 1819 to 1955. To organize this discussion, I will focus on Black opera companies, singers, and composers.

|

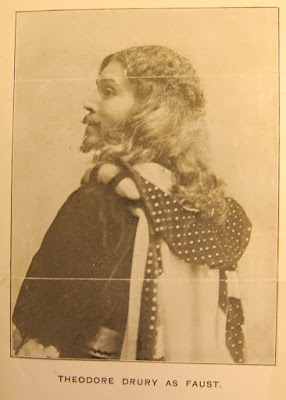

| A picture of Theodore Drury as Faust taken from a program for the 1902 performance by the Theodore Drury Grand Opera Company. |

EARLY 1800s–MID-1900s

Since opera basically remained segregated on stage until Marian Anderson’s historic performance at the Metropolitan Opera on January 7, 1955, the earliest cases we know of Black people performing in opera in the United States are in the all-Black companies that began after the Civil War. In addition to occasional operatic scenes and numbers performed in Black churches and civic venues, Black opera companies reveal the interest and presence of opera in the Black community right after slavery. Two big names that emerge are singer-impresarios Theodore Drury (1867–1943) and his Theodore Drury Grand Opera Company (1900–1907 and sporadically until 1938) and Mary Cardwell Dawson (1894–1962) with her National Negro Opera Company (1941–1962). Drury and Dawson were the first Black opera producers who launched Black companies that lasted several seasons in the US. With performances in New York City and Philadelphia, Theodore Drury was a baritone whose opera productions included scenes from Il trovatore (in 1889) and more complete versions of Aida, Carmen, Faust, Cavalleria rusticana, Pagliacci, and Il Guarany by Carlos Gomes. Mary Cardwell Dawson studied voice at the New England Conservatory and founded the Cardwell School of Music in Pittsburgh in 1927. Her award-winning choir (Cardwell Dawson Choir) led to the establishment of the National Negro Opera Company where she produced Aida, La traviata, and Faust as well as works by Black composers—Nathaniel Dett’s The Ordering of Moses and Clarence Cameron White’s Ouanga!Yet even earlier than the Civil War, Black involvement in opera includes vocalists who sang opera arias in concert and recitals. Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield (c. 1819–1876) was born into slavery, manumitted, and given voice lessons, ultimately becoming the first Black singer to have international success. Other Black opera singers of the 19th and early 20th centuries include Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones (1868–1933, also known as the “Black Patti”), Thomas Bowers (c. 1823–1885), Marie Selika Williams (c. 1849–1937), and several others Black singers, despite the nearly impossible odds against them. Sissieretta Jones toured the United States, Canada, Europe, and parts of the Caribbean. She sang for presidents Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt. From 1896–1915 she was the leading soloist of the Black Patti’s Troubadours, a troupe that performed vaudeville acts as well as arias and choruses from grand opera.

Operas by Black composers give voice to new narratives and present opportunities to work within the conventions of European opera as well as to develop the growing tradition of an original American opera at the turn of the 20th century. Recurring tropes and main topics begin to create a new aesthetic by using folk melodies, rhythms, and forms; specific locations (e.g., New Orleans, former plantations, Haiti, western African countries); and to multi-dimensional honorable portrayals of Black people in contrast to the negative stereotypes of minstrelsy. A few central themes have emerged in operas by Black composers from the end of the 19th century through the middle of the 20th century. The Tom Tom drum as a link to Africa (especially by the first generations coming of age during the Harlem Renaissance, born free after the Civil War) figures in Shirley Graham DuBois’s Tom Tom (1932) and William Grant Still’s Blue Steel (1934). Adaptations of Black Atlantic diasporic religions (such as Vodoun and connections to the supernatural through superstition and conjure) as a source of empowerment and resistance feature in Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha (1911), Harry Lawrence Freeman’s Voodoo (1914, rev. 1928), Clarence Cameron White’s Ouanga! (1932), and Still’s Minette Fontaine (1958).

|

| On Easter Sunday 1939, Marian Anderson performed on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in front of an audience of more than 75,000 people. |

Marian Anderson, 1897–1993

These singers, companies, composers, and compositions anchored the stage upon which Marian Anderson stood in her historic and groundbreaking career. The distinguished recital career of Roland Hayes (1887–1977), who toured Europe singing art songs by European and Black composers, made Anderson’s career in Germany easier. Through the work of other African American singers like Lillian Evanti (1890–1967) whose operatic repertory abroad included Délibe’s Lakmé and Violetta (La traviata) and Caterina Jarboro (1903–1986), who sang across genre in popular theatre as well as in opera in Europe as Aida and Selika (Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine), Anderson saw contemporary Black women singing in leading concert halls and opera houses in Europe. After being denied the chance to perform in Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the Revolution, Anderson was given permission to sing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on April 9, 1939, a concert in front of thousands and even more over the radio. Her historic debut on the Metropolitan Opera stage on January 7, 1955 as Ulrica in Verdi’s opera Un ballo in maschera trenchantly and symbolically desegregated opera stages in the United States as well as across the world. This led to a welcome, yet limited, opening of the opera house to more Black singers, artists, and audiences in subsequent decades. This powerful legacy serves as a firm foundation supporting the rise of many outstanding Black opera singers, composers, and producers, whose work we enjoy today. I look forward to sharing my thoughts on our current generation of artists in my next essay in the Blue program. |

| A portrait of Mary Cardwell Dawson, founder of the National Negro Opera Company. |

SPOTLIGHT: Saving the Legacy of Mary Cardwell Dawson

In recent years the performances and work of Mary Cardwell Dawson have gained new interests. The Victorian house where she founded the National Negro Opera Company in Pittsburgh has been added to the Most Endangered Places List by the National Trust for Historic Preservationists. What’s more, acclaimed mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves recently starred in the Glimmerglass production of The Passion of Mary Cardwell Dawson, a play with music composed by Carlos Simon and libretto by Sandra Seaton. Graves’ foundation has a lead role in saving and celebrating the legacy of this remarkable artist.Suggested Reading about Black opera

- And So I Sing: African American Divas of Opera and Concert, Grand Central Publishing (1990) by Rosalyn Story.

- “Becoming the ‘Black Swan’ in Mid-Nineteeth-Century America: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield’s Early Life and Debut Concert Tour,” Journal of the American Musicology Society, vol. 67, no. 1 (Spring 2014) by Julia J. Chybowski.

- Black Opera: History, Power Engagment, University of Illinois Press (2018) by Naomi André.

- “Class, Race, and Uplift in the Opera House: Theodore Drury and His Company Cross the Color Line,” Journal of Musicological Research, vol. 34 (2015) by Kristin Turner.

No comments:

Post a Comment